Apple announced Swift 4 as part of Xcode 9 at WWDC a few weeks ago. Although still in beta during the summer until its final release in September, this is the first version of the language that doesn’t break your code. It brings some really nice improvements and very much needed additions to existing Swift 3 features which you will learn all about in this article. So without any further ado, let’s dive in! 🙂

This article assumes that you already have some working knowledge of Swift 3. If you need a quick reminder of the most important Swift 3 and Swift 3.1 highlights and changes, check out my what’s new in Swift 3 and Swift 3.1 articles.

I will use Playground to go through the code change with you. If you want to fully understand the new features/changes of Swift 4, I suggest you to open Xcode 9 beta and create a new Playground file. Some of the examples in this article require the Foundation framework in order to work properly, so go ahead and import it before we begin anything if you want to try everything in a playground while reading:

import Foundation

JSON Encoding and Decoding

Let me begin by showing you one of the cool features in the new version of Swift. Swift 4 simplifies the whole JSON archival and serialization process you were used to in Swift 3. Now you only have to make your custom types implement the Codable protocol – which combines both the Encodable and Decodable ones – and you’re good to go:

class Tutorial: Codable {

let title: String

let author: String

let editor: String

let type: String

let publishDate: Date

init(title: String, author: String, editor: String, type: String, publishDate: Date) {

self.title = title

self.author = author

self.editor = editor

self.type = type

self.publishDate = publishDate

}

}

let tutorial = Tutorial(title: "What's New in Swift 4?", author: "Cosmin Pupăză", editor: "Simon Ng", type: "Swift", publishDate: Date())

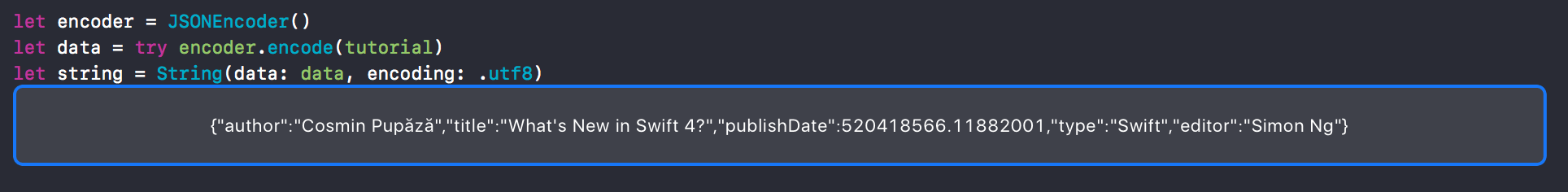

Your Tutorial class conforms to the Codable protocol, so let’s go ahead and encode your tutorial object:

let encoder = JSONEncoder()

let data = try encoder.encode(tutorial)

let string = String(data: data, encoding: .utf8)

You first create an encoder object with the JSONEncoder class designated initializer. Then you archive the tutorial into a data object using the try statement and the encoder’s encode(_:) method. Finally, you convert the data to a string using UTF-8 encoding. If you follow me using Playground, you will see the JSON output:

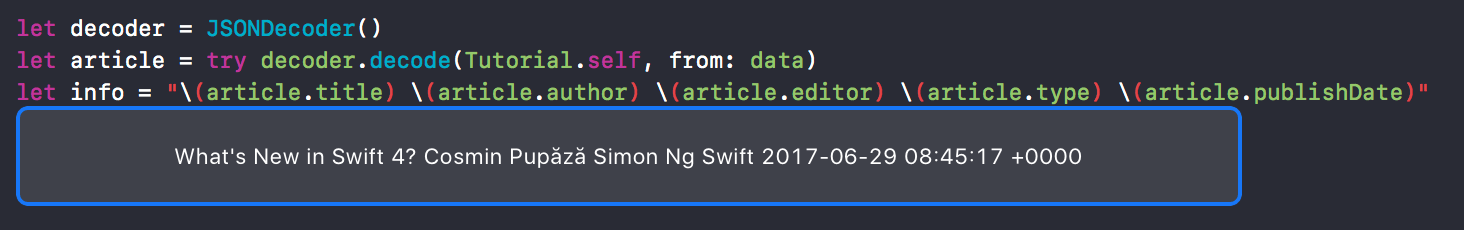

Now let’s see how to get back the initial tutorial object:

let decoder = JSONDecoder()

let article = try decoder.decode(Tutorial.self, from: data)

let info = "\(article.title) \(article.author) \(article.editor) \(article.type) \(article.publishDate)"

First of all you declare the decoder object with the JSONDecoder class initializer. Then you decode the encoded data inside a try block like before with the decoder’s decode(_: from:) method. Last but not least, you use string interpolation to generate a custom string using the article object’s properties. Now it’s so simple to decode JSON data.

Smarter Key Paths

Swift 4 makes it easier to access an object’s properties with key paths. Consider the following class implementation:

class Author {

let name: String

let tutorial: Tutorial

init(name: String, tutorial: Tutorial) {

self.name = name

self.tutorial = tutorial

}

}

let author = Author(name: "Cosmin Pupăză", tutorial: tutorial)

You use the previously created Tutorial class in order to define a certain tutorial for the author object. Now here’s how you get the author’s name using key paths:

let authorNameKeyPath = \Author.name

let authorName = author[keyPath: authorNameKeyPath]

You first create a key path with a backslash and then use the keyPath subscript to get the author object’s name.

But that’s not all – you may use key paths to go through the whole class hierarchy and determine the tutorial object’s title like this:

let authorTutorialTitleKeyPath = \Author.tutorial.title

let authorTutorialTitle = author[keyPath: authorTutorialTitleKeyPath]

You can even add a new key path to an already defined one using the key path’s appending(path:) method as follows:

let authorTutorialKeyPath = \Author.tutorial

let authorTutorialNameKeyPath = authorTutorialKeyPath.appending(path: \.title)

let authorTutorialName = author[keyPath: authorTutorialNameKeyPath]

I’ve left the best part at the end – using key paths in order to change property values:

class JukeBox {

var song: String

init(song: String) {

self.song = song

}

}

let jukeBox = JukeBox(song: "Nothing else matters")

let jukeBoxSongKeyPath = \JukeBox.song

jukeBox[keyPath: jukeBoxSongKeyPath] = "Stairway to heaven”

You first define the JukeBox class and create a jukeBox object with a new song to play. Then you define a key path for the song property and use it in order to change the song.

Mixing Classes with Protocols

You can combine protocols together in Swift 3 when creating constants and variables. Swift 4 goes one step further and lets you add classes to the mix using the same syntax. You may constrain a certain object to a class and a protocol in just one go the same way as in Objective-C.

Imagine that you are coding a drawing and colouring app. The main classes and protocols prototypes that you are using look like this:

protocol Drawable {}

protocol Colourable {}

class Shape {}

class Line {}

You create two base classes for shapes and lines and two protocols that handle both of the drawing and colouring corresponding logic. Now suppose that you want to define some specific types for your app:

class Circle: Shape, Drawable, Colourable {}

class Rectangle: Shape, Drawable, Colourable {}

class Square: Shape, Drawable, Colourable {}

class StraightLine: Line, Drawable {}

class DottedLine: Line, Drawable {}

let circle: Circle

let rectangle: Rectangle

let square: Square

let straightLine: StraightLine

let dottedLine: DottedLine

First, you create three concrete classes: Circle, Rectangle and Square which inherit from the Shape base class and conform to both the Drawable and Colourable protocols. Then you declare two derived classes: StraightLine and DottedLine that inherit the Line class and implement the Drawable and Colourable protocols as well. Finally, you define objects for each and every single class you have previously created.

The problem with this approach is that it complicates the class hierarchy by making way too many subclasses for each new type in your app. You could go ahead and simplify things a bit by combining the two protocols together:

let newCircle: Drawable & Colourable

let newRectangle: Drawable & Colourable

let newSquare: Drawable & Colourable

You make your objects adhere to both the Drawable and Colourable protocols with the & operator. You may go even one step further and simplify the syntax a little bit more by creating a type alias for your protocols:

typealias DrawableColourable = Drawable & Colourable

let anotherCircle: DrawableColourable

let anotherRectangle: DrawableColourable

let anotherSquare: DrawableColourable

Your objects conform to the DrawableColourable compound protocol, but it’s not enough because the initial problem still remains unsolved. Swift 4 to the rescue – add the base classes to the mix like this:

let brandNewCircle: Shape & Drawable & Colourable

let brandNewRectangle: Shape & Drawable & Colourable

let brandNewSquare: Shape & Drawable & Colourable

let brandNewStraightLine: Line & Drawable

let brandNewDottedLine: Line & Drawable

You create Shape and Line objects and make them implement their corresponding Drawable and Colourable protocols with the & operator. Your class hierarchy is short and sweet now and guess what – you may also create a type alias for the whole thing in order to simplify the syntax:

typealias DrawableColourableShape = Shape & Drawable & Colourable

typealias DrawableLine = Line & Drawable

let anotherNewCircle: DrawableColourableShape

let anotherNewRectangle: DrawableColourableShape

let anotherNewSquare: DrawableColourableShape

let anotherNewStraightLine: DrawableLine

let anotherNewDottedLine: DrawableLine

You define type aliases for the DrawableColourableShape and DrawableLine custom types and declare corresponding objects for them. Your drawing and colouring app design looks just great now – way to go! 🙂

One Sided Ranges

Swift 4 adds prefix and postfix versions for the half open range and closed range operators in order to create one sided ranges. Here is how you get the first half of a given array in Swift 3:

let array = [1, 5, 2, 8, 4, 10]

let halfIndex = (array.count - 1) / 2

let openFirstHalf = array[0..<halfIndex]

let closedFirstHalf = array[0...halfIndex]

You use the half open range and closed range operator to get the corresponding open and closed first half of the array. Both ranges start with the 0 index since you are beginning with the very first element of the array, so you can safely infer it without explicitly mentioning it in Swift 4 as follows:

let openFirstSlice = array[..<halfIndex]

let closedFirstSlice = array[...halfIndex]

You drop the range’s start index because you process all of the array’s elements up to the halfIndex corresponding one. Now let’s see how to return the second half of the array in Swift 3:

let nextIndex = halfIndex + 1

let lastIndex = array.count - 1

let openSecondHalf = array[nextIndex..<lastIndex + 1]

let closedSecondHalf = array[nextIndex...lastIndex]

Nothing new here – you use the half open range and closed range operators to go from where you left last time to the end of the array. Just like in the previous case, you don’t need to mention the array’s last element corresponding index for closed ranges in Swift 4:

let closedSecondSlice = array[nextIndex...]

You drop the range’s end index since you go from the nextIndex corresponding array element right to the very end of the array.

The one sided range operators let you create infinite sequences that start with any given value. This is how you display the array’s indexes and values in Swift 3:

for (index, value) in array.enumerated() {

print("\(index + 1): \(value)")

}

You print a tuple for each and every index and its corresponding value using a for in loop and the array’s enumerated() method. The array’s first index is always 0, so you should increase it by 1 in order to start with 1 instead. This isn’t necessary anymore in Swift 4:

for (index, value) in zip(1..., array) {

print("\(index): \(value)")

}

You use the zip(_: _:) function inside a for in loop in order to combine the one sided range of indexes with the array’s values – the first index is 1 now. Notice that although the index sequence is infinite, the loop stops when all of the array’s elements have been printed. This is the only way of avoiding to create an endless loop in this case: you should terminate it at some point so that it doesn’t go on and on like crazy.

One sided ranges work really well with pattern matching techniques in switch statements. There is only one caveat though – you must add a default case in order to make the switch exhaustive since ranges are infinite now:

let favouriteNumber = 10

switch favouriteNumber {

case ..<0:

print("Your favourite number is a negative one.")

case 0...:

print("Your favourite number is a positive one.")

default:

break

}

You use infinite ranges to test if your favourite whole number is either positive or negative by comparing it to 0. The ..<0 and 0... patterns model their corresponding (-∞, 0) and [0, +∞) intervals. Notice that the default case is never used here, so you just bail out of it with the break statement.

swap vs swapAt

The swap(_:_:) mutating method in Swift 3 takes two elements of a certain array and swaps them on the spot:

var numbers = [1, 5, 2, 8, 4, 10]

swap(&numbers[0], &numbers[1])

This solution has one major drawback: the swapped elements are passed to the function as inout parameters so that it can access them directly. Swift 4 takes a totally different approach by replacing the method with a swapAt(_:_:) one which takes the two elements corresponding indices and swaps them just as before:

numbers.swapAt(0, 1)

The swap(_:_:) function can also swap two given values in Swift 3 – you pass the values as inout arguments like you did in the previous case:

var a = 1

var b = 2

swap(&a, &b)

The swap(_:_:) function will be deprecated and completely removed in Swift 4, so you have two ways to replace it. The first approach uses another constant to perform the actual swap:

let aux = a

a = b

b = aux

The second solution takes the advantage of Swift built in tuples to implement the previous algorithm with only one line of code:

(b, a) = (a, b)

Improved Dictionaries and Sets

Dictionaries and sets are two useful data structures, but they have always lacked some important features in Swift 3, so Swift 4 improves them both. Let’s start with dictionaries since there are more changes there than in the case of sets.

First of all, here’s how you create a dictionary from an array of tuples in Swift 4:

let tupleArray = [("Monday", 30), ("Tuesday", 25), ("Wednesday", 27), ("Thursday", 20), ("Friday", 24), ("Saturday", 22), ("Sunday", 26)]

let dictionary = Dictionary(uniqueKeysWithValues: tupleArray)

You use the dictionary’s init(uniqueKeysWithValues:) initializer to create a brand new dictionary from a tuples array. Each tuple represents the average temperature of a certain day of the week, so the dictionary’s keys are the names of the days and its values are their corresponding temperatures.

If you have different arrays for the dictionary’s keys and values to begin with, you can still build the whole thing like this:

let keys = ["Monday", "Tuesday", "Wednesday", "Thursday", "Friday", "Saturday", "Sunday"]

let values = [30, 25, 27, 20, 24, 22, 26]

let newDictionary = Dictionary(uniqueKeysWithValues: zip(keys, values))

The zip(_:_:) function creates the previous array of tuples from the corresponding arrays. But what if you have only the values array and no keys instead? One sided ranges to the rescue all over again:

let anotherDictionary = Dictionary(uniqueKeysWithValues: zip(1..., values))

You create an infinite sequence that starts with 1 and combine it with the dictionary’s values in the zip(_:_:) function: the keys go now from 1 for Monday to 7 for Sunday – good job! 🙂

But what about duplicates? Swift 4 is smart enough to let you handle by yourself any duplicate values the dictionary might have like this:

let duplicatesArray = [("Monday", 30), ("Tuesday", 25), ("Wednesday", 27), ("Thursday", 20), ("Friday", 24), ("Saturday", 22), ("Sunday", 26), ("Monday", 28)]

let noDuplicatesDictionary = Dictionary(duplicatesArray, uniquingKeysWith: min)

You create a dictionary which has only unique keys with the dictionary’s init(_: uniquingKeysWith:) initializer. It uses a specific algorithm to choose the corresponding value for each and every duplicate key in the dictionary. In this case, if there are two different temperatures for a certain day of the week, you go with the smallest one of them.

But what if you want to merge some duplicates to an existing dictionary? Swift 4 has got you covered here as well:

let duplicateTuples = [("Monday", 28), ("Tuesday", 27)]

var mutatingDictionary = Dictionary(uniqueKeysWithValues: tupleArray)

mutatingDictionary.merge(duplicateTuples, uniquingKeysWith: min)

let updatedDictionary = mutatingDictionary.merging(duplicateTuples, uniquingKeysWith: min)

Adding elements to a dictionary comes in two flavours: you can either modify the original dictionary on the spot with the mutating merge(_: uniquingKeysWith:) method or create a completely new dictionary from scratch with the non-mutating merging(_: uniquingKeysWith:) one. The duplicates filtering algorithm works as in the previous case – feel free to try anything else and see what happens.

Dictionary subscripts in Swift 3 return the value of a corresponding key as an optional, so you use the nil coalescing operator to set default values for missing keys:

var seasons = ["Spring" : 20, "Summer" : 30, "Autumn" : 10]

let winterTemperature = seasons["Winter"] ?? 0

The requested season isn’t in the dictionary, so you set a default temperature for it. Swift 4 adds a brand new subscript for specific values of keys that don’t exist in the dictionary, so you don’t need the nil coalescing operator anymore in this case:

let winterTemperature = seasons["Winter", default: 0]

The custom subscript lets you update values of existing keys more easily. Here’s how you would do this in Swift 3 without it:

if let autumnTemperature = seasons["Autumn"] {

seasons["Autumn"] = autumnTemperature + 5

}

You first have to unwrap the optional value of the corresponding season’s name with the if let statement and then update it if it’s not nil. Now let’s see how it’s all done in Swift 4 with the default value subscript:

seasons["Autumn", default: 0] += 5

You combine the new subscript with the addition assignment operator in order to solve the task in just one line of code – now isn’t that something or what? 🙂

Both map(_:) and filter(_:) have been redesigned for dictionaries in Swift 4 because they return arrays, not dictionaries in Swift 3. For example, this is how you map the values of a given dictionary in Swift 3:

let mappedArrayValues = seasons.map{$0.value * 2}

You map the temperatures for the seasons dictionary from Celsius degrees to Fahrenheit ones using shorthand arguments. If you want to map the keys as well, you would do it like this in Swift 3:

let mappedArray = seasons.map{key, value in (key, value * 2)}

This approach creates an array of tuples out of the dictionary’s elements but it won’t work in Swift 4 because you can’t do tuple destructuring for closure parameters any longer (more about that in another section of the article). The first workaround uses the whole tuple as the map(_:) function’s argument:

let mappedArray = seasons.map{season in (season.key, season.value * 2)}

The second solution uses shorthand syntax instead:

let mappedArrayShorthandVersion = seasons.map{($0.0, $0.1 * 2)}

Both versions are OK overall, but you are still stuck with arrays instead of dictionaries after all, so let’s go ahead and fix this:

let mappedDictionary = seasons.mapValues{$0 * 2}

You map the original dictionary into a brand new dictionary which has the same structure as the initial one with the mapValues(_:) function – how cool is that? 🙂

Now here’s how you filter the values of a dictionary in Swift 3 with shorthand syntax:

let filteredArray = seasons.filter{$0.value > 15}

Only the temperatures above 15 make it into the filtered array. But what if we want a filtered dictionary instead? Swift 4 to the rescue once more:

let filteredDictionary = seasons.filter{$0.value > 15}

The code is exactly the same as in the previous case, but you have a filtered dictionary with the same structure as the original one this time – sweet! 🙂

Swift 4 enables you to split a dictionary into groups of values like this:

let scores = [7, 20, 5, 30, 100, 40, 200]

let groupedDictionary = Dictionary(grouping: scores, by:{String($0).count})

The dictionary’s init(grouping: by:) initialiser groups together the dictionary’s values by specific keys. In this case, you partition the scores array by the number of digits for each particular score like this:

[ 1: [7, 5], 2: [20, 30, 40], 3: [100, 200] ]

You may also rewrite the whole thing using trailing closure syntax as follows:

let groupedDictionaryTrailingClosure = Dictionary(grouping: scores) {String($0).count}

You extract the closure for the dictionary’s key out of the initializer because the closure is the initializer’s last argument in this case – really cool! 🙂

Swift 3 lets you create a dictionary with an initial capacity like this:

let ratings: Dictionary = Dictionary(minimumCapacity: 10)

You can store at least ten ratings in the ratings dictionary with the dictionary’s init(minimumCapacity:) initializer, but there’s no way of checking out for the current capacity or reserving more storage. Swift 4 saves the day once more:

seasons.capacity

seasons.reserveCapacity(4)

You get the dictionary’s current storage with the capacity property and create memory in order to store more elements with the reserveCapacity(_:) method.

That’s all about dictionaries. Both sets and dictionaries are collections under the hood, so let’s see what dictionary changes apply to sets as well.

Sets are a special case of arrays because they store only unique items. However, when you filter a set in Swift 3 you get an array, not a set:

var categories: Set = ["Swift", "iOS", "macOS", "watchOS", "tvOS"]

let filteredCategories = categories.filter{$0.hasSuffix("OS")}

You filter the categories set in order to get only the Apple technologies that are related to operating systems. Swift 4 returns a filtered set instead:

let filteredCategories = categories.filter{$0.hasSuffix("OS")}

The code is the same as in Swift 3, but the operating systems are stored in a set instead of an array this time.

You may create a set with a default capacity in Swift 3 like this:

let movies: Set = Set(minimumCapacity: 10)

The movies set stores a minimum of ten movies to start with. Swift 4 takes everything to the next level by declaring the set’s capacity and defining extra space for its items:

categories.capacity

categories.reserveCapacity(10)

You can store more categories in the set and access its capacity anytime. That’s it for sets! 🙂

Private vs Fileprivate in Extensions

Swift 3 uses the fileprivate access control modifier in order to make the important data of a certain class available anywhere outside of the class as long as you actually access it from the very same file. This is how it all works in the case of extensions:

class Person {

fileprivate let name: String

fileprivate let age: Int

init(name: String, age: Int) {

self.name = name

self.age = age

}

}

extension Person {

func info() -> String {

return "\(self.name) \(self.age)"

}

}

let me = Person(name: "Cosmin", age: 31)

me.info()

You create an extension for the Person class and use string interpolation to access its private properties in the info() method. This is such a common pattern in Swift, so you can now use the private access level instead of the fileprivate one in Swift 4 in order to access class properties in an extension as if you would do it inside the class itself:

class Person {

private let name: String

private let age: Int

// original code

}

NSNumber Improvements

Swift 3 doesn’t typecast an NSNumber to an UInt8 properly:

let x = NSNumber(value: 1000)

let y = x as? UInt8

The right value of y should be nil in this case because the Uint8 type begins with 0 and goes up to 255 only. Swift 3 takes a totally different approach by computing the remainder instead: 1000 % 256 = 232. This weird behaviour has been fixed in Swift 4, so y is nil now as you would expect in the first place.

Unicode Scalars for Characters

You can’t access the unicode scalars of a certain character directly in Swift 3 – you have to convert it to a string first like this:

let character: Character = "A"

let string = String(character)

let unicodeScalars = string.unicodeScalars

let startIndex = unicodeScalars.startIndex

let asciiCode = unicodeScalars[startIndex].value

You determine the character’s ASCII code from the unicode scalars of the corresponding string. Swift 4 adds a unicodeScalars property to characters, so you can access it directly now:

let unicodeScalars = character.unicodeScalars

// original code

Improved Emoji Strings

Swift 3 doesn’t determine the number of characters in emoji strings correctly:

let emojiString = "👨👩👧👦"

let characterCountSwift3 = emojiString.characters.count

The number of characters for the string should be 1 because there is only one emoji character in there, but Swift 3 returns 4 in this case. Swift 4 fixes this:

let characterCountSwift4 = emojiString.count

As you can see, you can access the count property directly on the string itself because strings are treated as collections in Swift 4 – more about that in another section of the article.

Multiple Line Strings

You declare strings on multiple lines in Swift 3 by adding \n symbols for each and every new line and escaping all double quotes in the text like this:

let multipleLinesSwift3 = "You can \"escape\" all of the double quotes within the text \n by formatting it with a \"\\\" backslash before each and every single double quote that appears out there \n and insert inline \\n symbols before each and every new line of text \n in order to display the string on multiple lines in Swift 3.”

Swift 4 takes a completely different approach for multiple line strings by using triple quotes instead, so you don’t have to escape double quotes anymore:

let multiLineStringSwift4 = """

You can display strings

on multiple lines by placing a

\""" delimiter on a separate line

both right at the beginning

and exactly at the very

end of it

and don't have to "escape" double quotes

"" in Swift 4.

"""

Generic Subscripts

Swift 4 lets you create generic subscripts: both the subscript’s parameters and return type may be generic. Here’s a non-generic Swift 3 subscript that determines the maximum and minimum values in a given array:

// 1

extension Array where Element: Comparable {

// 2

subscript(minValue: Element, maxValue: Element) -> [Element] {

// 3

var array: [Element] = []

// 4

if let minimum = self.min(), minimum == minValue {

// 5

array.append(minValue)

}

// 6

if let maximum = self.max(), maximum == maxValue {

array.append(maxValue)

}

// 7

return array

}

}

This is what’s happening over here, step by step:

- You create an extension on the

Arrayclass and use thewherekeyword in order to constrain its elements to implement theComparableprotocol. - The subscript takes two parameters which are of the same type as the array’s items and returns an array created from its corresponding arguments.

- You define the final array which you will return from the subscript later on – it’s empty to begin with.

- You unwrap the original array’s minimum value inside an

if letstatement and check if it’s equal to the subscript’s first parameter. - You add the minimum value to the final array declared earlier if the previous test succeeds.

- You repeat steps 4 and 5 for the initial array’s maximum value and the subscript’s second parameter this time.

- You return the final array and you’re done.

Now here’s how the subscript looks like in action for arrays of numbers and strings:

let primeNumbers = [3, 7, 5, 19, 11, 13]

let noMinOrMaxNumber = primeNumbers[5, 11] // []

let onlyMinNumber = primeNumbers[3, 13] // [3]

let justMaxNumber = primeNumbers[7, 19] // [19]

let bothMinAndMaxNumbers = primeNumbers[3, 19] // [3, 19]

let greetings = ["Hello", "Hey", "Hi", "Goodbye", "Bye"]

let noFirstOrLastGreeting = greetings["Hello", "Goodbye"] // []

let onlyFirstGreeting = greetings["Bye", "Hey"] // ["Bye"]

let onlyLastGreeting = greetings["Goodbye", "Hi"] // ["Hi"]

let bothFirstAndLastGreeting = greetings["Bye", "Hi"] // ["Bye", "Hi"]

That’s pretty cool, but you can also make it work for sequences in Swift 4 like this:

extension Array where Element: Comparable {

// 1

subscript(type: String, sequence: T) -> [T.Element] where T.Element: Equatable {

// 2

var array: [T.Element] = []

// 3

if let minimum = self.min(), let genericMinimum = minimum as? T.Element, sequence.contains(genericMinimum) {

array.append(genericMinimum)

}

if let maximum = self.max(), let genericMaximum = maximum as? T.Element, sequence.contains(genericMaximum) {

array.append(genericMaximum)

}

return array

}

}

Let’s go over what’s changed since last time:

- The subscript is generic now. It takes two parameters: a generic sequence and the sequence’s type as a string and returns a generic array: its elements must conform to the

Equatableprotocol. - The final array is generic in this case as well.

- You create the generic versions of the array’s unwrapped minimum and maximum values and check if the sequence contains both of them.

The subscript is really powerful now – this is how you use it with specific sequences like arrays and sets of numbers and strings:

let noMinOrMaxArray = [5, 11, 23]

let numberFirstArray = primeNumbers["array", noMinOrMaxArray] // []

let onlyMinNumberSet: Set = [3, 13, 2, 7]

let numberFirstSet = primeNumbers["set", onlyMinNumberSet] // [3]

let justMaxNumberArray = [7, 19, 29, 10]

let numberSecondArray = primeNumbers["array", justMaxNumberArray] // [19]

let bothMinAndMaxSet: Set = [3, 17, 19]

let numberSecondSet = primeNumbers["set", bothMinAndMaxSet] // [3, 19]

let noFirstOrLastArray = ["Hello", "Goodbye"]

let stringFirstArray = greetings["array", noFirstOrLastArray] // []

let onlyFirstSet: Set = ["Bye", "Hey", "See you"]

let stringFirstSet = greetings["set", onlyFirstSet] // ["Bye"]

let onlyLastArray = ["Goodbye", "Hi", "What's up?"]

let stringSecondArray = greetings["array", onlyLastArray] // ["Hi"]

let bothFirstAndLastSet: Set = ["Bye", "Hi"]

let stringSecondSet = greetings["set", bothFirstAndLastSet] // ["Bye", "Hi"]

Strings as Collections

Strings are collections in Swift 4, so you can now treat them like arrays or sequences and simplify certain tasks. For example, this is how you would filter a given string in Swift 3:

let swift3String = "Swift 3"

var filteredSwift3String = ""

for character in swift3String.characters {

let string = String(character)

let number = Int(string)

if number == nil {

filteredSwift3String.append(character)

}

}

You use a for in loop to process the string’s characters one by one. Each character is first converted to a string and then you check if the corresponding string isn’t actually a number under the hood. Finally, you add the corresponding character to the filtered string if the previous test succeeds.

Swift 4 lets you do all this by using functional programming techniques directly on the string itself instead:

let swift4String = "Swift 4”

let filteredSwift4String = swift4String.filter{Int(String($0)) == nil}

Swift 3 returns a string when defining substrings from a given string:

let swift3SpaceIndex = swift3String.characters.index(of: " ")

let swift3Substring = swift3String.substring(to: swift3SpaceIndex!)

You get the corresponding substring with the string’s substring(to:) method. Swift 4 takes a completely different approach by adding a brand new Substring type to the mix:

let swift4SpaceIndex = swift4String.index(of: " ")

let swift4Substring = swift4String[..<swift4SpaceIndex!]

You use one sided ranges to determine the substring in this case – its type is Substring, not String this time. Both the String and Substring types conform to the StringProtocol protocol, so they behave exactly the same.

Improved Objective-C Inference

Swift 3 automatically infers the @objc annotation for selectors and key paths that use properties or methods which are also available in Objective-C:

class ObjectiveCClass: NSObject {

let objectiveCProperty: NSObject

func objectiveCMethod() {}

init(objectiveCProperty: NSObject) {

self.objectiveCProperty = objectiveCProperty

}

}

let selector = #selector(ObjectiveCClass.objectiveCMethod)

let keyPath = #keyPath(ObjectiveCClass.objectiveCProperty)

You create a custom class that inherits from NSObject and define selectors and key paths for its properties and methods. Swift 4 requires you to manually add the previous annotation yourself so that everything still works correctly:

class ObjectiveCClass: NSObject {

@objc let objectiveCProperty: NSObject

@objc func objectiveCMethod() {}

// original code

}

Tuple Destructuring in Closures

Swift 3 lets you work directly with a tuple’s components if they are used as parameters in a given closure. Here’s how you implement this feature in order to map an array of tuples using functional programming techniques:

let players = [(name: "Cristiano Ronaldo", team: "Real Madrid"), (name: "Lionel Messi", team: "FC Barcelona")]

let tupleDestructuring = players.map{name, team in (name.uppercased(), team.uppercased())}

You make use of the closure’s arguments in order to uppercase the player’s name and team. This isn’t possible anymore in Swift 4, but there are two workarounds instead. The first one uses the whole tuple for the closure’s parameter like this:

let tuple = players.map{player in (player.name.uppercased(), player.team.uppercased())}

The second solution uses shorthand arguments for brevity:

let shorthandArguments = players.map{($0.0.uppercased(), $0.1.uppercased())}

Constrained Associated Types in Protocols

You may constrain associated types inside protocols in Swift 4:

protocol SequenceProtocol {

associatedtype SpecialSequence: Sequence where SpecialSequence.Element: Equatable

}

First you create a custom protocol and you add an associated type to it that conforms to the Sequence protocol. Then you use a where clause in order to constrain the elements of the sequence: they should all implement the Equatable protocol.

Conclusion

That’s all about Swift 4. I hope you like this tutorial and enjoy all the changes in Swift 4. In the meantime, please let me know if you have any questions or issues. Happy Swifting! 🙂